Introduction

Many patients requiring long term enteral nutrition have neurological disorders, such as motor neurone disease (MND) or Huntington’s disease (HD). In our experience, a proportion of these individuals may struggle to tolerate enteral feeding despite optimising medical management and excluding obvious gastrointestinal pathology.

In MND, prolonged reduced mobility, weakness of abdominal and pelvic muscles, diets low in fibre, dehydration and use of certain medications such as glycopyrronium, methantheline or propantheline may indirectly reduce bowel motility and prolong colonic transit time1. Therefore, constipation and overflow ‘spurious’ diarrhoea may be common in these patients2.

Both constipation and diarrhoea can affect the nutritional status of enterally fed patients. There are some studies that suggest the importance of good nutritional status for survival and quality of life of patients with MND1. Therefore, finding the most optimal enteral feed is paramount.

In patients with HD, it has been demonstrated that a significant proportion may experience reflux and oesophagitis3.

Studies in mice also suggest that the gastrointestinal tract is thinner in those with HD compared to controls, thereby resulting in a degree of malabsorption4. However, further research is required to confirm if this is also true in humans.

While there have been numerous research studies on nutritional status and the best ways of delivering nutritional support in these patients, evidence and guidelines around enteral feed choice is lacking. Furthermore, there are no local protocols regarding tube feed choices for patients with neurological conditions available in our trust.

The following case studies discuss the pragmatic management of gastrointestinal symptoms in long-term enterally-fed patients with MND and HD.

Case Study 1: Motor Neurone Disease

Background:

- 77 year–old female patient admitted to West Cumberland Hospital in January 2016.

- Presented with high troponin levels, NSTEMI (non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction) and possible aspiration pneumonia.

- Patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) due to increasing shortness of breath and a worsening productive cough.

- The diagnosis of MND was confirmed after a series of investigations and review by a specialist neurologist.

Past medical history:

- High blood pressure

- Asthma

- Cervical spinal surgery in 2015 (spondylosis causing spinal cord compression).

January 2016 Initial Assessment Intubated, sedated and nasogastric tube (NGT) in situ. Commenced on Osmolite® HP at 70ml/hr x 20 hours.

February 2016:

Constipation and bloating noted.

(History of constipation and laxative use prior to admission).

Feed changed to fibre-containing formula: Jevity® at 50ml/hr x 20hrs

Developed loose, green stools (non-infective).

Laxatives omitted.

March 2016:

Peptide feed trialled – Vital® 1.5 at 50ml/hr x 20hrs.

(1.5kcal/ml, casein and whey based peptide formula with 64% of fat from MCT. Osmolarity 487 mOsm/L).

Non-compliance with laxatives and risk of overflow diarrhoea when constipated.

April 2016:

Vital® 1.5 feeding rate increased gradually to 80ml/hr over 20 hours.

Ongoing bloating and watery Type 7 stools of a light brown colour, containing mucous.

Feed changed to Peptamen® HN: 80ml/hr x 20hrs. 1.33 kcal/ml, 100% whey peptide formula with 70% of fat from MCT. Osmolarity 350 mOsm/L.

Change of stool consistency to yoghurt consistency (Type 6) and better bowel control. Previous frequent ‘accidents’ on other feeds. Feed rate increased to 120ml/hr in preparation for discharge.

Ongoing type 6 stools with no pain, wind or bloating reported when laxatives were taken regularly. Occasional cramps, flatus and diarrhoea which was mostly likely related to a combination of inactivity, MND and the effect of different drugs, like muscle relaxants and anti-muscarinic drugs.

New feeding regime for discharge: 300ml Peptamen® HN boluses QDS.

Frequency of bowel movements decreased from 5-6 times a day, to 2–3 times a day.

Case Study 2: Huntington’s Disease

Patient Information:- 45 year-old female patient with Huntington’s disease.

- Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in-situ since September 2016.

- Bolus-fed due to jerky movements.

- Recent history of diarrhoea, constipation and vomiting. Managed with laxatives, enemas and change of feed to Vital® 1.5: (1.5kcal/ml, casein and whey based peptide formula with 64% of fat from MCT. Osmolarity 487 mOsm/L).

February 2016

Received hand-over of dietetic care from colleague. Ongoing Type 7 stools.

Movicol® reduced to once daily.

Trial of Optifibre® with no obvious improvement

Change of feed to Peptamen® AF 200ml x 5 boluses daily for 1 week. (Peptamen AF: 1.5 kcal/ml, 100% whey peptide formula with 50% of fat from MCT. Osmolarity 380 mOsm/L). No change in symptoms observed, therefore returned to Vital® 1.5

June 2016

Volume of diarrhoea increased (non-infective).

It was felt the patient may have needed a longer trial of Peptamen® AF. Feed changed back to Peptamen® AF 200ml x 5 daily and to continue Movicol® at current dose (once daily) unless becoming constipated.

August 2016

Over one month, stool consistency gradually improved and was no longer green in colour.

October 2016

Carers reported Type 5–6 stools.

Smell, colour and quantity of stool all normalised.

Discussion

Gastrointestinal symptoms in this patient group are multifactorial. It can be difficult to ascertain the exact cause or to establish the effect of new interventions. Working with the MDT to optimise medical management and rule out underlying issues is paramount.

When these strategies fail to bring about adequate relief from symptoms, a change of enteral formula may be indicated. Even if symptoms cannot be fully resolved, there may be an opportunity to improve the patient’s quality of life. As previously mentioned, my patients did not tolerate the usual feeds of choice and I had to look further into enteral feed compositions in order to prevent decline in nutritional status. I chose Peptamen® products primarily because they are 100% whey based and there is some evidence to suggest improved transit time on whey based feeds in neurological patient groups5,6.

100% whey peptide formulas have been shown to improve gastric emptying which may be important in those with vomiting, reflux and regurgitation, particularly due to the risk of aspiration pneumonia5. Secondly, both Peptamen® HN and Peptamen® AF have a raised energy and protein content, enabling me to meet the patient’s nutritional requirements in a smaller volume. Thirdly, Peptamen® HN and AF have the lowest osmolarity compared to the rest of the available peptide feeds in our trust. The formulas that are close to being iso-osmotic or isotonic help promote gastric emptying more than high osmotic feeds7. This may help to reduce the risk of aspiration. I had to compromise with the price of Peptamen® in order to improve the patient’s quality of life.

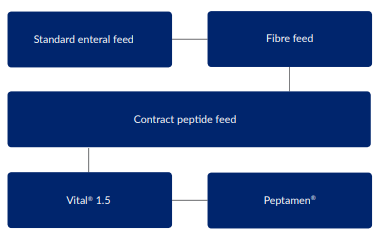

At West Cumberland hospital, if our contract peptide feed is not tolerated by a patient, Peptamen® is considered. However in our community setting Peptamen® feeds may be considered straight away. Since writing this case study I have successfully used Peptamen® products in other enterally fed patients with neurological conditions.

The diagram below shows the decision making process for managing feeding intolerance in our trust:

Conclusion

Enteral feeding intolerance is not confined to the acute setting, nor to specific disease states. Its management often requires a pragmatic approach due to individual patient factors. In our experience, a whey peptide formula may be useful if other management strategies have failed, in order to help promote comfort and quality of life.

References- Heffernan, C., Jenkinson, C., Holmes, T., Feder, G., Kupfer, R., Leigh, P.N., McGowan, S., Rio, A., and Sidhu, P. (2004). Nutritional management in MND/ALS patients: an evidence based review. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Other Motor Neuron Disorders 5 (2), 72-83.

- Travis, S.P., Ahmad, T., Collier, J., and Steinhart, H. (2005). The gut in systemic Disorders. Pocket Consultant: Gastroenterology. 3rd ed. pp. 376-386. Blackwell Publishing.

- Andrich J.E., Wobben, N., Klotz, P., Goetze, O., and Saft, C. (2009). Upper gastrointestinal findings in Huntington’s disease: patients suffer but do not complain Journal of Neural Transmission. 116, 1607-1611.

- Van der Burg, J.M.M, Winqvist, A., Aziz, M.A., Maat-Schieman, M.L.C., Roos, R.A.C., Bates, G.P., Brundin, P., Bjorkvist, M., and Wierup, N. (2011). Gastrointestinal dysfunction contributes to weight loss in Huntington’s disease mice. Neurobiology of Disease. 44, 1–8.

- Alexander, D.D., Bylsma, L.C., Elkayam, L., and Nguyen, D. (2016). Nutritional and health benefits of semi-elemental diets: A comprehensive summary of the literature. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 7 (2), 306-319.

- Savage, K., Kritas, S., Schwarzer, A., Davidson, G., and Omari, T. (2012). Whey- vs Casein-Based Enteral Formula and Gastrointestinal Function in Children With Cerebral Palsy. Journal of Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition. 36, Suppl. 1.

- Stroud, M., Duncan, H., and Nightingale, J. (2003). Guidelines for enteral feeding in adult hospital patients. Gut. 52, (Suppl VII), vii1-vii12. Available from: http://www.bsg.org.uk/ pdf_word_docs/enteral.pdf [Accessed:31.05.17].

Many patients requiring long term enteral nutrition have neurological disorders, such as motor neurone disease (MND) or Huntington’s disease (HD). In our experience, a proportion of these individuals may struggle to tolerate enteral feeding despite optimising medical management and excluding obvious gastrointestinal pathology. In MND, prolonged reduced mobility, weaknes...