Introduction/overview

Major trauma refers to significant or multiple injuries that could result in death or severe disability, sustained from a traumatic insult such as a road traffic collision, fall, sporting accident, or physical assault. It is the leading cause of death and major disability in people aged under 45 years in the UK.1 Critically injured patients are often managed on an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and require individualised and closely monitored nutrition support for optimal recovery. Traumatic injuries induce substantial catabolic responses, resulting in high nutritional requirements. At the same time, trauma patients are at risk of feeding intolerances and interruptions to feed delivery, making it challenging to meet these increased demands. The nutritional requirements of major trauma patients with different traumatic injuries and their associated feeding issues will be discussed below. Major trauma centres comprise of an extremely heterogeneous population; patients come from all backgrounds and age groups, have a mix of comorbidites, and have a wide range of injuries in various combinations. Common injuries involve the head, spinal cord, long-bones, pelvis, face and chest; and also include amputations, degloving injuries and abdominal trauma. Personalised nutrition support plans must be developed with consideration toward route of feeding, around the injury sites. Although the baseline nutritional status of trauma patients varies, there tends to be less chronic disease and malnutrition on admission compared with other ICU populations, but severe traumatic injuries induce significant catabolism putting patients at high risk of rapid undernutrition. Alongside this, the complex nature of the surgical management of trauma patients often requires frequent trips to theatre and other interruptions to enteral feeding, limiting the time available to provide enteral nutrition (EN). For this reason, patients admitted to a major trauma centre require a different nutritional approach to the management of other ICU patients.

Early enteral feeding

As with all ICU patients, enteral feeding is optimal, because of its ability to attenuate the inflammatory response, promote healing, minimise complications, reduce loss of muscle mass and ultimately support the rehabilitation of trauma patients.2 EN should commence as soon as a patient is haemodynamically stable, in order to achieve the non-nutritional benefits and minimise the protein and energy deficits that frequently occur during the early stages of critical illness.3 These non-nutritional benefits include maintaining structural and functional gut integrity to reduce the risk of increased intestinal permeability, attenuation of oxidative stress and the inflammatory response, and decreasing insulin resistance.2 Indeed, patients who start EN within 24 hours of admission have reduced intestinal permeability and are less likely to develop severe multi-organ failure.4 It is vital to ensure that these non-nutritional benefits of EN are not overlooked by surgical and anaesthetic colleagues, especially when faced with patients who may appear ‘well nourished’ at baseline.

Meeting requirements & reducing feeding deficits

Nutritional requirements are frequently higher than those of other ICU populations and although standard ICU feeding algorithms are necessary to establish early EN, it is important to note that they will not meet the needs of most trauma patients (especially given that a large number of trauma patients are young, males who tend to have lean or muscular builds). Although concern has been raised regarding the potential dangers of overfeeding on ICU, in reality it is uncommon for trauma patients to receive more than 80% of prescribed feeds, therefore underfeeding is common and of a greater concern in this population.

Studies show that nutritional deficits accrued during ICU stay has a negative effect on both short-term and hospital-related outcomes. Significant underfeeding has been demonstrated to result in increased complication rates, particularly in terms of infections, and longer ICU and hospital stays.3 Moreover, there is an emerging body of evidence that underfeeding on ICU can have long-term functional implications in terms of rehabilitation for surgical trauma patients.

A recently published study by Yeh and colleagues, demonstrated that critically ill surgical patients who accumulated feeding deficits of more than 6000 kcal or 300g protein within the first 14 days of their admission, were three-times more likely to require on going nursing or rehabilitation care rather than being discharged home.5 It appears that improved nutrition delivery during the early stages of ICU care may lead to better functional outcomes, which is crucial to this patient group.

Given the raised nutritional needs of major trauma patients, achieving feeding targets can be challenging. Key reasons for feed interruptions include feeding intolerance and fasting for diagnostic procedures, surgery and airway management.6 Minimising fasting times for procedures should be a priority in all ICUs. In fact, pre-operative fasting in intubated patients tolerating EN may be completely unnecessary. Reduced-fasting protocols have been implemented in many ICUs and can result in fewer feed interruptions and improved enteral nutrition delivery, with no increase in adverse events such as aspiration pneumonia.7,8

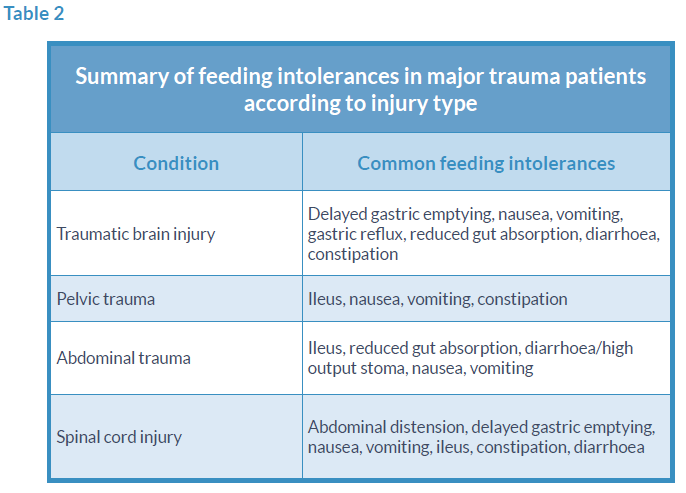

Feeding intolerances vary according to the injury type, however the most common intolerances in major trauma patients include diarrhoea, delayed gastric emptying with high gastric residual volumes, vomiting and abdominal distension. These are discussed below with examples from the different injury types.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

The ICU management of patients with severe TBI is targeted at optimising brain perfusion, oxygenation and avoiding secondary brain injuries.9 Brain injuries can result in increased intracranial pressure (ICP), which is usually closely monitored with an ICP bolt. In order to optimise patients after a head injury, they are usually kept sedated and ventilated on the ICU. In addition to heavy sedation medical interventions involve paralysis, cooling and tight control of blood glucose levels and cardiovascular function.

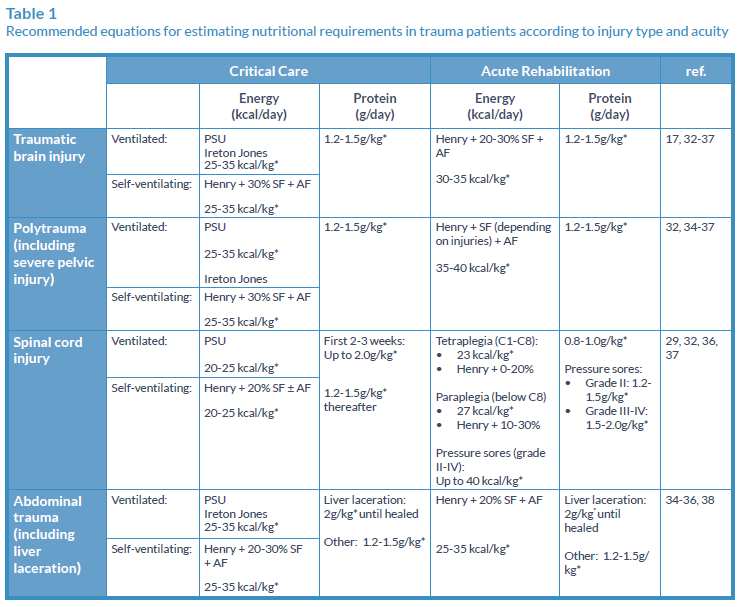

Table 1 outlines the nutritional requirements for TBI patients, however, medical interventions such as sedation, cooling and paralysis will all impact on energy expenditure. For this reason, regular reassessment of nutritional requirements by a dietitian is necessary.

Nutrition also represents a cornerstone of TBI management, and early adequate nutritional intake is associated with a reduction in infectious complications, mortality and may lead to earlier neurological recovery.3,10-12 However, establishing adequate EN can be challenging, with approximately 50% of patients exhibiting intolerance to EN.13

TBI can lead to several physiological complications including gastrointestinal dysfunction such as impaired gut motility and reduced absorption.13,14 Motility disorders in brain injured patients include gastroesophageal reflux related to a reduced tone in the lower oesophageal sphincter and delayed gastric emptying.15-18

Delayed gastric emptying is common in TBI; with sedation, paralysis, raised intracranial pressure, cooling and raised sodium all implicated as contributing factors.19 Despite the challenges of establishing EN, it should still remain the gold standard, and as such, strategies to optimise EN delivery should be considered prior to initiation of parenteral nutrition (PN). Strategies include the use of prokinetic drugs, alternative feed formulations, higher tolerance thresholds for gastric residual volumes (GRVs) and the use of small bowel feeding.

Propofol is a commonly used sedative for trauma patients, and is suspended in lipid emulsion which provides 1.1 kcal/ml. Trauma patients are often on high doses of propofol to maintain adequate sedation. This can contribute significantly to energy intake, so high protein formulas are therefore required to meet protein requirements without exceeding energy requirements. Unfortunately, the issue of delayed gastric emptying is often exacerbated by heavy sedation, and high-protein feeds may therefore be poorly tolerated. Whey-based formulas (100%) have been shown to have faster gastric emptying than casein-based formulas.20 High-protein, 100% whey- based formulas are recommended for optimal gastric tolerance.21

Pelvic Trauma

Patients suffering from complex pelvic injury with associated retroperitoneal haematomas appear to have an increased risk of developing paralytic ileus, although the mechanism is unclear. This could be related to the trauma itself, since severe pelvic injury generally requires a high-velocity trauma and is therefore indicative of higher injury severity. It may also be related to surgical fixation procedures (internal and external), or manipulation and handling of the gut incidental to surgery.

It is difficult to predict which patients may develop a prolonged ileus, although this is more likely in injuries involving the posterior pelvic structures.22 Early initiation of EN appears to be of benefit, via NG or NJ tube if necessary, however in prolonged ileus PN may be indicated.

Patients who have external fixation of their pelvic fractures will be restricted in their ability to sit up and mobilise, and therefore frequently experience reduced appetite, nausea and bladder/ bowel dysfunction. These patients should be identified early for nutritional assessment, with regular monitoring and oral nutritional support if required.

Abdominal Trauma

Decisions regarding timing and route of feeding in patients with abdominal trauma should be considered on an individual basis and discussed with the surgical team, with close monitoring of gastric aspirates, bowels and intra-abdominal pressure (if indicated).23 Early enteral feeding remains the goal, and has been found to be well tolerated24, with a significantly lower incidence of septic morbidity in those enterally fed after blunt and penetrating trauma.24,25

Abdominal trauma can lead to increased intra-abdominal pressures (>12mmHg) and occasionally abdominal compartment syndrome (>20mmHg). A study of 77 hospital patients to determine normal intra-abdominal pressure found mean intra-abdominal pressure was 6.5mmHg (range 0.2-16.2mmHg).26

Patients with abdominal compartment syndrome or an open abdomen can be fed enterally,27 however there may be concerns regarding ileus/bowel oedema, aspiration and risk of bowel necrosis, for which PN should be considered.28

Spinal Cord Injury (SPI)

Patients with SCI have reduced metabolic activity due to denervated muscle, therefore energy requirements are often much lower in relation to other trauma patients.29 However, the protein intake required to minimise the obligatory negative nitrogen balance that occurs during this phase is very high (up to 2g/kg/body weight). For this reason, high protein formulas are often indicated.

Optimal timing for initiation of enteral feeding in SCI differs from recommendations for non-SCI trauma patients. In acute tetraplegia, there appears to be no difference in outcomes when feeding is initiated later (after 120 hours) compared with early feeding.30 Indeed, in some SCI patients, EN can be very poorly tolerated in the first few days of admission as a result of ileus. Paralytic ileus can occur in SCI due to spinal shock, surgery, other traumatic injuries and medications. For this reason, in isolated SCI, EN should be initiated within 48-72 h of admission. In the case of polytrauma including a SCI, early initiation of EN is the gold standard (especially when TBI is also present), with close monitoring for signs of feeding intolerance.

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) is sometimes required in the initial management of SCI due to compromised respiratory muscle function. Oral intake is often compromised in this situation (inadequate and/or unsafe), therefore NG tube feeding is required until ventilatory support can be weaned. Abdominal distension and discomfort, with associated nausea and vomiting can be a side effect of NIV (due to air being forced into stomach) – which may require gastric decompression. This can either be achieved by regular aspiration (or free drainage) of the NG tube alongside intermittent or bolus feeding, or with the use of a decompression valve (such as a Farrell valve).

SCI can result in a range of functional gastrointestinal deficits affecting feed tolerance, including delayed gastric emptying and prolonged gut transit time. Constipation is also common, and can be life-threatening in this group due to autonomic dysreflexia, therefore strict bowel-management protocols are required to ensure regular defecation. These include consideration of laxatives, suppositories, digital stimulation regimens, manual evacuation and modification of fluid and fibre intake.

Pressure ulcers are common and can be difficult to heal once established, resulting in higher nutritional requirements (see Table 1). Again, high-protein feeds are useful for these patients. In the case of perineum/sacral ulcers, it is imperative that diarrhoea is avoided and/or controlled, with a bowel management system if necessary, to avoid infection. Peptide-based feeds are recommended for the management of diarrhoea in ICU patients requiring EN.31

Conclusion

Major trauma patients have raised nutritional requirements, which can vary dramatically according to injury type and clinical management. Early EN is vital to reduce complications and optimise recovery. However, achieving energy and protein targets can be challenging due to frequent interruptions to feeding and gastrointestinal tolerance issues, such as delayed gastric emptying, reflux, ileus, constipation and diarrhoea. Consideration should be given to the use of prokinetic drugs, switching to alternative feed formulations, and alternative feeding routes to help overcome these intolerances and provide optimum nutritional management.

References

- online 30/11/15] https://www.tarn.ac.uk/Home.aspx (2015).

- McClave SA, Martindale RG, Rice TW. Feeding the Critically Ill Patient. Critical Care Medicine 42, 2600–2610 (2014).

- Villet, S, Chiolero, R. L, Bollmann, M. D, Revelly, J.-P, Cayeux R N, M.-C, Delarue, J, Berger, M. M. Negative impact of hypocaloric feeding and energy balance on clinical outcome in ICU patients. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland), 24(4), 502–9 (2005).

- Kompan L, Kremžvar B, Gadžvijev E, Prosek M. Effects of early enteral nutrition on intestinal permeability and the development of multiple organ failure after multiple injury. Intensive Care Medicine 25(2), 157–161 (1999).

- Yeh DD, Fuentes, E, Quraishi, S, Cropano, C, Kaafarani, H, Lee, J, Velmahos, G. Adequate Nutrition May Get You Home: Effect of Caloric/Protein Deficits on the Discharge Destination of Critically Ill Surgical Patients. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (2015) EPub ahead of print DOI 10.1177/0148607115585142.

- Passier RH, Davies AR, Ridley E, McClure J, Murphy D, Scheinkestel CD. Periprocedural cessation of nutrition in the intensive care unit: opportunities for improvement. Intensive Care Medicine, 39(7), 1221–6 (2013).

- Pousman RM, Pepper C, Pandharipande P, Ayers GD, Mills B, Diaz J, Jensen G. Feasibility of Implementing a Reduced Fasting Protocol for Critically Ill Trauma Patients Undergoing Operative and Nonoperative Procedures. JPEN 33(2), 176–180 (2009).

- Segaran E, Barker I, Hartle A. Optimising enteral nutrition in critically ill patients by reducing fasting times. Journal of the Intensive Care Society, 0(0), 1-6 (2015).

- Helmy A, Vizcaychipi M, Gupta A. Traumatic brain injury: Intensive care management. British Journal of Anaesthesia 99(1), 32-42 (2007).

- Taylor SJ, Fettes SB, Jewkes C, Nelson RJ. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial to determine the effect of early enhanced enteral nutrition on clinical outcome in mechanically ventilated patients suffering head injury. Critical Care Medicine 27, 2525–2531 (1999).

- Perel P, Yanagawa T, Bunn F, Roberts I, Wentz R, Pierro A. Nutritional support for head-injured patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD001530 (2006).

- Wang X, Dong Y, Han X, Qi X-Q, Huang C-G, Hou L-J. Nutritional support for patients sustaining traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. PloS One, 8(3), e58838 (2013).

- Tan M, Zhu J-C, Yin H-H. Enteral nutrition in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: reasons for intolerance and medical management. British Journal of Neurosurgery, 25(1), 2–8 (2011). Neurosurgery, 25(1), 2–8 (2011).

- Krakau K, Omne-Pontén M, Karlsson T, Borg J. Metabolism and nutrition in patients with moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Brain Injury 20(4), 345–367 (2006).

- Kao CH, ChangLai SP, Chieng PU, Yen TC. Gastric emptying in head-injured patients. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 93(7), 1108–1112 (1998).

- Norton JA, Ott LG, McClain C, Adams L, Dempsey RJ, Haack D, Young AB. Intolerance to enteral feeding in the brain-injured patient. Journal of Neurosurgery, 68(1), 62–66 (1988).

- Weekes E, Elia M. Observations on the patterns of 24-hour energy expenditure changes in body composition and gastric emptying in head-injured patients receiving nasogastric tube feeding. Journal of Parenteral & Enteral Nutrition, 20(1), 31–37 (1996).

- Olsen B, Hetz R, Xue H, Aroom KR, Bhattarai D, Johnson E, Uray K. Effects of traumatic brain injury on intestinal contractility. Neurogastroenterology and Motility : The Official Journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 25(7), 593–e463 (2013).

- Ott L, Young B, Phillips R, McClain C, Adams L, Dempsey R, Ryo UY. Altered gastric emptying in the head-injured patient: relationship to feeding intolerance. J.Neurosurg. 74, 738–742 (1991).

- Fried MD, Khoshoo V, Secker DJ, Gilday DL, Ash JM, Pencharz PB. Decrease in gastric emptying time and episodes of regurgitation in children with spastic quadriplegia fed a whey-based formula. The Journal of Pediatrics 120(4 Pt 1), 569–72 (1992).

- Khoshoo V, Brown S. Gastric emptying of two whey-based formulas of different energy density and its clinical implication in children with volume intolerance. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 56, 656-658 (2002).

- Hurt AV, Ochsner JL, Schiller WR. Prolonged ileus after severe pelvic fracture. American Journal of Surgery 146(6), 755–7 (1983).

- Bejarano N, Navarro S, Rebasa P, García-Esquirol O, Hermoso J. Intra-abdominal Pressure as a Prognostic Factor for Tolerance of Enteral Nutrition in Critical Patients. JPEN. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 37(3), 352–360 (2012).

- Dissanaike S, Pham T, Shalhub S, Warner K, Hennessy L, Moore EE, Cuschieri J. Effect of Immediate Enteral Feeding on Trauma Patients with an Open Abdomen: Protection from Nosocomial Infections. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 207(5), 690–697 (2008).

- Kudsk KA, Croce MA, Fabian TC, Minard G, Tolley EA, Poret HA Brown RO. Enteral versus parenteral feeding. Effects on septic morbidity after blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma. Annals of Surgery 215(5), 503–11; discussion 511–3 (1992).

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11270882.

- Cothren CC, Moore EE, Ciesla DJ, Johnson JL, Moore JB, Haenel JB, Burch JM. Postinjury abdominal compartment syndrome does not preclude early enteral feeding after definitive closure. American Journal of Surgery 188(6), 653–658 (2004).

- Friese RS. The open abdomen: definitions, management principles, and nutrition support considerations. Nutrition in Clinical Practice : Official Publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 27(4), 492–498 (2012).

- American Dietetic Association (ADA) Spinal Cord Injury. Evidence-based nutrition practice guideline. American Dietetic Association, Guideline NGC-7375 (2009).

- Dvorak MF, Noonan VK, Bélanger L, Bruun B, Wing P. C, Boyd MC, Fisher C. Early versus late enteral feeding in patients with acute cervical spinal cord injury: a pilot study. Spine, 29(9), E175–80 (2004).

- Martindale RG, Mcclave SA, Vanek V W, Mccarthy M, Roberts P, Taylor B, Cresci G. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Critical Care Medicine 37(5), 1–30 (2009).

- Jacobs DG, Jacobs DO, Kudsk KA, Moore FA, Oswanski MF, Poole GV Sinclair KE. Practice Management Guidelines for Nutritional Support of the Trauma Patient for the EAST Practice Management Guidelines Work Group. J. Trauma 57, 660–679 (2004).

- Bruder N, Dumont JC, Francois G. Evolution of energy expenditure and nitrogen excretion in severe head-injured patients. Critical Care Medicine 19(1), 43–48 (1991).

- Ishibashi N, Plank LD, Sando K; Hill GL. Optimal protein requirements during the first 2 weeks after the onset of critical illness. Critical Care Medicine 26:1529-1535 (1998). 34.

- Frankenfield D. Energy expenditure and protein requirements after traumatic injury. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 21, 430–437 (2006).

- Frankenfield DC, Coleman A, Alam S, Cooney RN. Analysis of estimation methods for resting metabolic rate in critically ill adults. JPEN. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 33(1), 27–36 (2009).

- Frankenfield D. Validation of an equation for resting metabolic rate in older obese, critically ill patients. JPEN. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 35(2), 264–269 (2011).

- Johnson J. Liver disease and nutritional support in adults. PEN Group A Pocket Guide To Clinical Nutrition. Third Edition, Chapter 16 (2004).

Major trauma refers to significant or multiple injuries that could result in death or severe disability, sustained from a traumatic insult such as a road traffic collision, fall, sporting accident, or physical assault. It is the leading cause of death and major disability in people aged under 45 years in the UK.1 Critically injured patients are often managed on ...