Introduction/overview

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a virus that attacks the immune system specifically targeting CD4 cells, white blood cells which play a major role in protecting against infection. As the virus progresses and the CD4 count decreases there is an increased risk of certain infections referred to as ‘opportunistic infections’ (OIs). The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a major site of infection in HIV patients, diarrhoea being the most common GI symptom increasing in frequency and severity as immune function deteriorates. The most common HIV associated diarrhoeal pathogens include: Cryptosporidium, non-tubercular Mycobacteria, Microsporidium bacteria and Cytomegalovirus (CMV).1 Of these pathogens Cryptosporidium and CMV will be the focus of this case study.

Cryptosporidium is a gastrointestinal parasitic OI and is a major cause of diarrhoea and malnutrition in HIV patients.2 It most commonly affects the distal small bowel showing mucosal atrophy and small erosions within the bowel wall. It is transmitted through the oral faecal routes, ingestion of contaminated water or food and by direct person to person or animal to person contact. The main symptoms include watery diarrhoea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and fever.

Cytomegalovirus is the most frequent opportunistic gastric infection normally involving the oesophagus and the colon. It is spread through bodily fluids such as saliva or urine and belongs to the herpes family of viruses. When the colon is affected by CMV, it causes intestinal inflammation, erosion and ulceration resulting in severe malabsorption particularly in immunocompromised individuals. As the virus progresses, it can potentially lead to bowel ischaemia and transmucosal necrosis resulting in perforation and peritonitis.3

In patients with HIV/AIDS the risk of acquiring Cryptosporidium and CMV is associated with the degree of immunosuppression, measured by CD4 counts. A CD4 count of <200 per mm3 increases the risk of contracting these gastrointestinal OIs. Patients with advanced AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) (CD4 <50 cells per mm3), particularly in the absence of Antiretroviral therapy (ART), can have severe diarrhoea that can persist for months, resulting in severe dehydration, weight loss, extended hospitalisation and increased mortality.4

There is little research into how to deal with such GI conditions from a nutritional perspective. However, ESPEN guidelines 2006 suggest that if normal food intake and optimal use of oral nutritional supplements cannot achieve sufficient energy supply, then tube feeding is indicated.5 With this in mind careful selection of an enteral formula is needed in order to maximise absorption and prevent further exacerbation of GI symptoms.

Patient’s background/medical history/weight history

A 32 year old gentleman was admitted with chronic diarrhoea, weight loss and abdominal pain over six months. He also complained of shortness of breath. His past medical history: HIV positive (diagnosed 2010, not on Antiretroviral therapy), previous CMV and hypertension.

His symptoms gradually worsened on admission. He was diagnosed with Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) and commenced on antibiotics. Stool sample results were positive for Cryptosporidium and he commenced on appropriate treatment. Colon biopsy results showed CMV positive cells and duodenal biopsies showed Cryptosporidial duodenitis.

The diarrhoea persisted on admission which resulted in a severe depletion in electrolytes, in particular sodium, potassium, magnesium, and phosphate which were replaced daily. Oral nutrition support was initiated within the first week of admission; however as diarrhoeal symptoms persisted and nutritional status deteriorated, nasogastric (NG) feeding was indicated. NG feeding was commenced two weeks into admission; there was a delay in initiating feeding due to obtaining patient consent. At first line Vital® 1.5 (Abbott Nutrition) was used due to being semi-elemental and higher in medium chain triglycerides (MCT). Tolerance to Vital® 1.5 became an issue with an increase in vomiting and little reduction in the frequency of the diarrhoea. The deterioration in the patient’s clinical condition and nutritional status meant an alternative enteral feed was required, in addition to maximising anti-diarrhoeals and antiemetics.

The patient’s CD4 count continued to deteriorate and CMV continued to multiply within the bowel resulting in his diarrhoea worsening. The feed was then altered to another peptide formula high in MCT: Peptamen® (Nestlé Health Science), which has a lower osmolarity. Bowel frequency improved and was maintained for five days; in addition his vomiting subsided. Unfortunately his CD4 count and CMV continued to worsen and diarrhoeal losses were severe. Electrolytes depleted severely despite supplementation and the patient required critical care observation. Parenteral nutrition (PN) was indicated at this point. Peptamen® was continued at a low rate (10ml/hr building up to 30ml/hr) alongside PN.

PN and continuous Peptamen® administration continued for three weeks and PN stopped once the diarrhoea resolved. Peptamen® feeding continued for a further week while the patient’s oral intake gradually improved.

After three months in hospital bowel frequency and consistency was much improved, Cryptosporidium was eradicated and CMV within the bowel under control. He was discharged home with nil follow up from the dietitians as nutritional status was much improved and he was meeting estimated nutritional requirements.

Relevant data

Weight

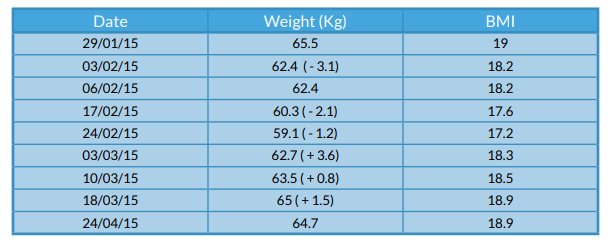

On admission the patient was 65.6kg with a BMI of 19kg/m2. The patient reported a total weight loss of approximately 11kg within the past month. During admission, he lost a total of 6.4kg and gradually improved towards the end of his admission.

Figure 1 - Weight changes

Blood results

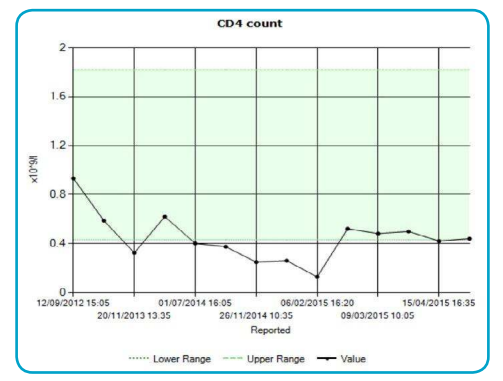

Gradual decline in the patient’s CD4 count since admission can be seen in Figure 2. This increased patient susceptibility to opportunistic infections and the infections already present increased in severity, as can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 2 - CD4 count

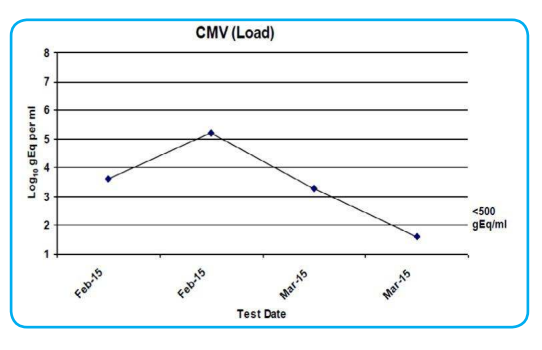

CMV serology was regularly tested throughout admission. A sharp rise can be seen on 25/02/15 in line with when the patient’s CD4 count started to decline from the beginning of February (See Figure 3). At this point his symptoms worsened considerably (see Figure 4 bowel frequency).

Figure 3

Bowels

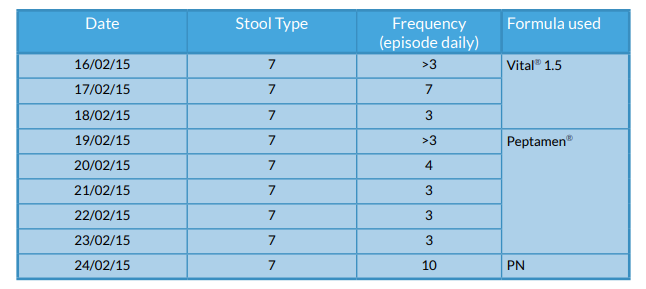

Stool charts were kept using the accredited Bristol Stool Chart. Figure 4 shows the time period when he was NG fed. Variable charts were kept while on PN.

Figure 4 - Stool frequency and formula used

Nutritional problems and dietetic intervention

- Total weight loss of 14% prior to admission. Further decline in weight during admission (6.4kg)

- Minimal oral intake

- Gastrointestinal symptoms including vomiting and diarrhoea

- Maintain gut integrity

- Electrolyte disturbances

- High risk of refeeding syndrome

Oral nutritional supplements were commenced as first line nutrition support and he was treated as at a high risk of refeeding syndrome, in view of prolonged poor oral intake and percentage weight loss.

NG feeding was eventually indicated in view of persistent minimal intake and declining weight, aiming to optimise nutrition. Two different enteral feeds were trialled, one being Peptamen®, in view of GI symptoms. Estimated nutritional requirements were not met through either feed before having to resort to PN; the main aims at this point were to optimise nutritional status and manage gastrointestinal symptoms.

Peptamen®, through the NG, ran in tandem with PN and gradually the patient was weaned off PN as Peptamen® was titrated up accordingly over a three week time period. After three weeks, the patient’s oral intake had improved and PN was stopped. Peptamen® was increased in order to supplement his oral intake, giving 50% of his estimated energy requirements. As oral intake continued to improve Peptamen® was appropriately weaned down and eventually stopped.

Reasoning

Both the duodenum and colon were affected by specific gastrointestinal opportunistic infections which impaired absorption of feed. In theory high MCT feeds are absorbed higher up the GI tract, therefore potentially minimising further diarrhoea and lower osmolarity of a feed can also positively affect absorption.

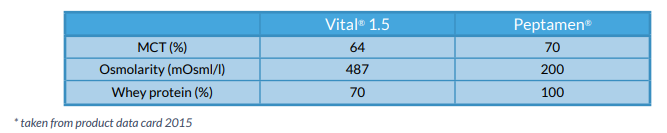

Comparing the two formulae profiles, Peptamen® appeared to be the most advantageous in regards to absorption. (See Figure 5)

Figure 5 - Comparison of feeds

Although PN was indicated, Peptamen® was used alongside in view of maintaining gut integrity and to avoid further aggravating the already inflamed bowel. Furthermore Peptamen® was better tolerated when trialled; vomiting ceased and stool frequency decreased.

Discussion

There is much debate over what feed composition to use, when it comes to feed intolerance in enterally fed patients with a condition that involves malabsorption. Undernutrition alongside Cryptosporidium causes mucosal disruption, reduced absorptive surface and increased proinflammatory cytokine response.6 CMV causes similar bowel inflammation affecting absorption.

Gastrointestinal opportunistic infections with severe malabsorption require aggressive nutrition support and many studies support the use of MCTs as a dietary fat source, in comparison to the usual polymeric formulas. High MCT feeds are absorbed quickly in the upper gastrointestinal tract and transported directly into the portal circulation,7 therefore relieving pressure on the distal bowel. Many studies have documented the positive results of using MCTs for patients with diseases and clinical conditions that interfere with long chain trigylyceride (LCT) digestion and absorption that are found in polymeric feeds.7 The 1.5 kcal/ml semi elemental feed saw a slight reduction in stool frequency from seven episodes per day of Type 7 stools, to 3-4 episodes daily after three days of feed, however nil improvement was seen with vomiting.

Whey-based enteral formulas, such as Peptamen®, have been postulated to reduce gastroesophageal reflux and accelerate gastric emptying.8 The majority of the studies were based on infants and children; however positive results were reported on whey-based formulas having a significant reduction in vomiting compared with those on the casein-based formula.9

There is limited information available on whether an increase in osmolarity can be related to enteral feeding related diarrhoea; however it is known that osmolarity influences the osmotic balance between the intestinal lumen and the vascular system.10 The more hypertonic a feed, the more it draws water into the GI tract, which theoretically can cause diarrhoea, vomiting and abdominal cramps. Furthermore low osmotic feeds have been found to cause less delayed gastric emptying compared to high osmotic feeds,11 which can reduce reflux/vomiting.

Enteral nutrition is preferred to Parenteral as it is more physiologically normal and has fewer complications.12 Nutrition into the gut prevents mucosal atrophy, a decrease in endotoxin translocation and maintains gut barrier function.12 Furthermore ESPEN guidelines 2006 suggest that enteral feeding is indicated in HIV patients with diarrhoea, as it has a positive impact on stool frequency, and consistency, indicating that MCT containing formulae are advantageous.5

There is similar efficacy for parenteral nutrition; however, some literature suggests that parenteral nutrition using fat emulsions may impair immune function through accumulation of fat globules within the macrophage system and may inhibit cell-mediated immunity.13 Furthermore the severity of immunosuppression may increase the risk of septic complications relating to PN and possibly increase the risk of secondary infections.14 There are limited studies in regards to the efficacy of PN in HIV/AIDS patients, however it is an alternative that has proved its efficacy in the management of chronic digestive disease.14

Available literature suggests that supplementation of EN with PN can be beneficial in reducing mucosal atrophy and increased intestinal permeability, with consequent reduction in the incidence of gut translocation in severe GI symptoms when sole EN cannot be maintained effectively due to condition.15

Conclusion

It is evident from this case that HIV infected patients with GI opportunistic infections need to be considered at an early stage for enteral feeding. Difficulties arise within this patient group particularly around the stigma attached to the virus. It therefore took some time for the patient to comply with NG feeding as he associated this with a prolonged hospital stay.

Nutritional status deteriorated rapidly as CD4 count decreased and GI symptoms worsened. Looking at the enteral feeds used with this patient and their effect on stool frequency, Peptamen® may have been a more appropriate feed to use first line to help reduce the nutritional losses.

Aggressive nutrition support managed to sustain this patient through treatment of severe gastrointestinal infections. Although PN was needed for a short time period, a 100% whey-based peptide feed was used alongside and eventually solely supplemented the patient’s oral intake, which rectified vomiting, improved bowel frequency and eventually increased the patient’s weight by 5.9kg.

References

- Bhaijee, F. et al. (2011). Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Gastrointestinal Disease: Common Endoscopic Biopsy Diagnoses. Patholog Res Int. 2011: 247923.

- Badoui. L. et al (2013). Intestinal cryptosporidiosis in HIV-infected patients in the department of infectious diseases. BMC Infectious diseases. Vol. 14 (sup. 2) P. 52.

- Heuman, D.M. (2014). Cytomegalovirus Colitis. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/173151-overview.

- O’Connor, R. et al (2011). Cryptosporidiosis in patients with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. Vol. 25: 549-560.

- Ockenga, J. et al(2006). ESPEN Guidelines on enteral nutrition: Wasting in HIV and other chronic infectious diseases. ESPEN Guidelines.

- Coutinho, B.P. et al (2008). Cryptosporidium infection causes undernutrition and, conversely, weanling undernutrition intensifies infection. J. Parasitol. 2008 December; 94(6):1225-1232.

- Craig, C.B. (1997). Decreased Fat and Nitrogen Losses in Patients with AIDS Receiving Medium-Chain-Triglyceride-Enriched Formula Vs Those Receiving Long-Chain-Triglyceride-Containing Formula. Journal of the American Dietetic Association Volume 97, Issue 6, June 1997, Pages 605–611.

- Savage et al (2012). Whey- vs Casein-Based Enteral Formula and Gastrointestinal Function in Children With Cerebral Palsy. J Parenter Enteral Nutr January 2012 vol. 36 no. 1 suppl 118S-123S.

- Fried MD et al (1992). Decrease in gastric emptying time and episodes of regurgitation in children with spastic quadriplegia fed a whey-based formula. Journal Of Paediatrics. Vol 120. P 569-572

- Schater, L. et al (2009). Osmolarity of modified enteral tube feeds for adults in hospitals across the western cape province. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Vol. 22(2):81-87.

- Stroud et al (2003). Guidelines for enteral feeding in adult hospital patients. Vol 52:vii1-vii12 doi:10.1136/gut.52.suppl_7.vii1.

- Lloyd, D.A.J. and Powell-Tuck, J. (2004). Artificial Nutrition: Principals and Pratice of Enteral Feeding. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. Vol 17(2): 107-118.

- Singer et al (1992). Clinical & Immunologic effects of lipid-based parenteral nutrition in AIDS.Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Vol. 16(2):165- 167.

- Melchior et al (1996). Efficacy of a 2 month total parenteral nutrition in AIDS patients. A controlled randomised prospective trial. The French multicentre total parenteral cooperative group study. AIDS. Vol:Apr;10(4):379-84.

- Peter J.V. et al (2005). A meta analysis of treatment outcomes of early enteral versus early parenteral nutrition in hospitalized patients. Crit Care Med 2005 Vol. 33, No. 1.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a virus that attacks the immune system specifically targeting CD4 cells, white blood cells which play a major role in protecting against infection. As the virus progresses and the CD4 count decreases there is an increased risk of certain infections referred to as ‘opportunistic infections’ (OIs). The gastrointestinal (GI) tr...